“My work amounted to a futile attempt to save us from who we are.” This is a quaint statement on the tendencies of humankind, as discussed in a book with so many facets as only purpose and perception have. I’m talking about Annihilation by Jeff VaderMeer.

Let’s get this book undone.

Introduction

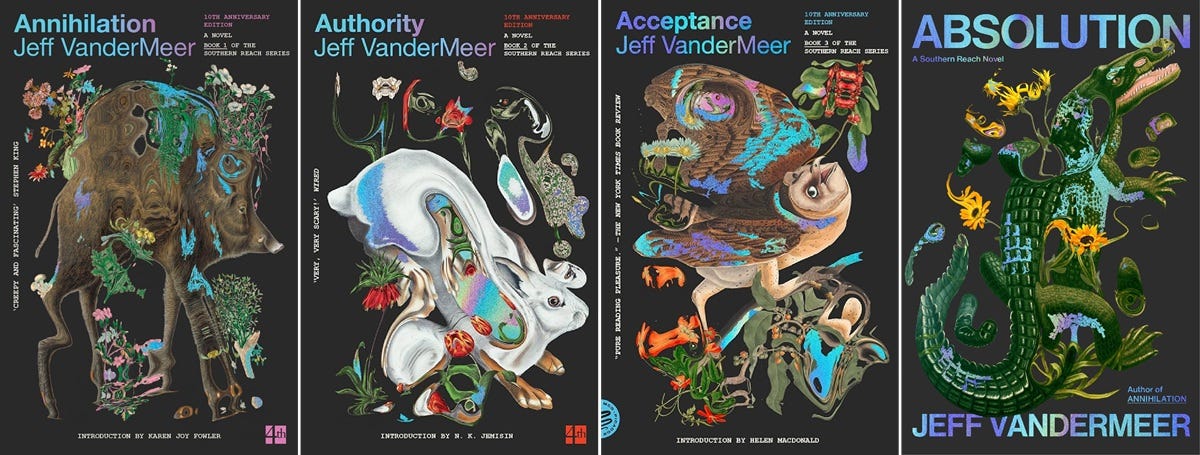

Hello everyone, and welcome to Books Undone. I’m your host, Livia J. Elliot, and today we are discussing Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer. This is the famous first book of the Southern Reach quartet, often labelled as ’new weird’ and ’ecofiction’—but I think of it as cosmic horror with an existential touch.

For those who don’t know him, Jeff VanderMeer is an American author and one of the most prominent faces of the new weird genre. His writing is generally described as “ecofiction”—a literary genre that explores environmental issues and the relationship between humanity and the environment through fiction1.

VanderMeer actually began writing in the 1980s, being a prolific contributor to small-presses; at that time, he focused on horror and fantasy short stories. City of Saints and Madmen (2001) is one of his earliest short-story collections to become renown. Several of his novels were set on the world that began in that collection, including Finch (published in 2009), which later became a Nebula Finalist for Best Novel.

However, due to the publication of Annihilation, VanderMeer’s fame grew. This book was received very well by critics, and it won both the Nebula Award and the Shirley Jackson Award for Best Novel, both in 2014. Since VanderMeer wrote the first three books back-to-back—namely, Annihilation, Authority, and Acceptance—they were all published in 2014. Not long after their quick publication, the entire series became a finalist for the 2015 World Fantasy Award, and the 2016 Kurd-Laßwitz-Preis. However, the trilogy was expanded into a quartet when the last book on the series, Absolution, was released in 2024.

That said, and before we move forward, let me make some disclaimers.

First, there are spoilers in this episode; I found it very hard to explain the theme of the book without diving into its plot, so we will start with a quirky plot summary (alongside some clues!) before diving into the thematic analysis… and from there into its philosophical considerations.

Second, what you will hear is my subjective interpretation of Annihilation, particularly focused around the themes of perception and existential meaning. It may not be what the author intended, and you may disagree. That’s okay. We all have different opinions.

Plot Summary

Let us begin with a quick refresher summary of the plot. I will hint at some curious things as we go.

Annihilation follows a group of researchers working for Southern Reach—a mysterious organisation sending periodic expeditions into Area X. While it is not clear where exactly Area X is, we know it is in Earth, and delimited by a Border. It’s near the shore, it may be expanding, and it all seems to have begun close to a Lighthouse after an Event. The expedition we’re following in this book is Expedition 12.

The expedition is composed of a surveyor, an anthropologist, a psychologist, and a biologist. The latter is the main character, and we are reading her own journal of the expedition.

Something quaint is that nothing here has a name. We have the Event, the Border, the Lighthouse, and then the Crawler and the Tower… but that’s it; those are descriptors, not actual names. Likewise, the characters do not have names, just professions. We never discover how the biologist is called, and as she writes her journal, she makes a painstaking effort to refer to her significant other as “my husband” without never naming him.

It sounds odd… but there is a reason for it. One the biologist explained as follows:

I would tell you the names of the other three, if it mattered, but […] we were always strongly discouraged from using names. We were meant to be focused on our purpose and “anything personal should be left behind”. Names belonged to where we had come from, not to who we were while embedded in Area X.

We know that names are important to us humans, not only for identification purposes, but also because how they relate to our identity. A person’s name is often seen as a marker of their identity, affecting an individual’s self-acceptance, and even being considered as the ‘ultimate control element’ over our memory2.

Removing someone’s names is akin to stripping someone of their individuality and selfhood. This is what Southern Reach did by asking them to “be focused on [their] purpose”: it tasked the team with leaving their self behind by narrowing them down into a function—as if they were loosing their individuality to become part of Area X. Remember this idea; we’ll come back to it.

However: what is Area X?

Within the book, Area X was described as a “transitional environment”. These are biologically complex zones “where terrestrial and marine processes interact, leading to unique sedimentary conditions and depositional features”3. To quote from the book itself, the Biologist explains that:

[Area X] transitioned several times, meaning that it was home to a complexity of ecosystems. In few other places could you still find habitat where, within the space of walking only six or seven miles, you went from forest to swamp to salt marsh to beach. In Area X, I had been told, I would find marine life that […] swam far up the natural canals formed by the reeds, sharing the same environment with otters and deers.

Weird, don’t you think? Marine life, like dolphins, swimming in canals alongside otters? It sounds like a plot-hole (especially because the biologist makes no comment about it), but it’s actually a clue to something bigger. This simple comment about wildlife is already subtly challenging the reader’s perception of Area X, including how we believe it could work—it is not a ’normal’ transitional environment, but something a bit unexplainable.

The last detail to review, is the books’ opening line—which is also a challenge to perception, and an important location within Area X.

The biologist begins her journal by saying: “The tower, […] plunges into the earth in a place just before the black pine forest begins.” But… doesn’t that sound like a tunnel? Why would you call it a tower if it “plunges into the earth”? Even the biologist herself reflects on this incoherence, stating that: “I don’t know why the word tower came to me, given that it tunneled into the ground.”

Theme Intro

So up to here, by simply reviewing the setting and plot, we already have two clues worth remembering:

(a) the extreme transitional environments—namely, the dolphins swimming in canals with the otters—that are not the norm in Earth, and,

(b) the so-called tower that actually tunnels into the ground.

From those two clues, we can suspect that our perception and understanding of Area X is being challenged. As readers, we are being eased into a quote-on-quote ’new normal’ within Area X.

What if I told you that I think Annihilation is cosmic horror?

Cosmic horror, also known as eldritch horror or lovecraftian horror, originated with H.P. Lovecraft, renown for the Cult of Cthulu (among other works). This subgenre emphasises the horror of the unknowable and the incomprehensible; it is riddled with themes of cosmic dread, non-human influences on humanity, inevitability, and the risks associated with scientific discovery. It is not ‘horror’ in the sense of ‘spooky’ or ‘scare jumps’, but the looming existentialist realisation that we, humans, are infinitesimal and almost irrelevant in a universe that exceeds us. As Moriah Richard (managing editor of Writers’ Digest) said, “many cosmic horror stories […] challenge the characters’ sense of reality”4.

That is exactly what Annihilation sets to do—to challenge the characters’ sense of reality while within Area X. It does so through three reality-altering challenges:

The failure of language, since it is a scaffolding to make the unknown known.

The breakdown of sensory perception as a tool to craft meaning.

A reality that exceeds (and refuses) our anthro-centric worldview.

Once we cover those three, we’ll link it to the cosmic dread—the realization of humanity’s insignificance and the incomprehensible nature of the universe—to understand how the loss of identity and purpose within Annihilation leads to dissolution of the self.

Let’s begin with the failure of language

Language is fundamental to us humans. Every bit of progress we have made throughout history, is thanks to our use of language and how it enabled communication. It is such a crucial tool for us humans, that many thinkers have argued that large differences in language lead to large differences in experience and thought. This is known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis which, in its weak version, states that a language’s structure influences a speaker’s perceptions without strictly limiting or obstructing them5.

In other words, we humans don’t just describe the world—we construct it through language, and so it is fundamental to our understanding of reality6. If we can’t put something into words, we can’t fully understand it—just approximate it with inaccurate words.

Let’s see how this plays out in Annihilation.

The biologist writes that she used to observe and document frogs, promptly noting that: “I had never talked to the frogs; I despised anthropomorphising animals.”

If you think of it, we are constantly anthropomorphising animals due to our limited language. For example, we approximate the meaning of a dog’s wagging tail using human emotions and label them as alert or friendly or stressed or angry, simply because it’s easier to communicate. The biologist, though, claims to hate this quote-on-quote ‘shortcut’ or ‘approximation’.

However, as soon as she goes down the tower, she finds words written with moss in the wall. When she gets closer to the words, she describes them as follows:

The curling filaments were all packed very close together and rising out from the wall. […] Other things existed in this miniature ecosystem. Half-hidden by the green filaments, most of these creatures were translucent and shaped like tiny hands embedded by the base of the palm. Golden nodules capped the fingers on these ‘hands’.

Methinks she just did exactly what she claimed to hate doing: she anthropomorphised fungi by describing it as ‘hands’ with ‘fingers’.

It sounds like a contradiction, isn’t it? Especially because the biologist doesn’t reflect on it, instead continuing to anthropomorphise stuff. For example, whenever they are at their encampment near dusk the team hears a noise, which she describes as “a low, powerful moaning.” But ‘moan’ is “a long, low sound of pain, suffering, or another strong emotion”—a markedly human noise! Yet just as before, she doesn’t think of the possible contradiction.

Let me give you one last example. Once the biologist leaves the camp to travel to the Lighthouse, she encounters a formation of moss, and proceeds to sample it. She writes in her journal:

I had a need to document what I had found, and […] I cut a piece of the moss from the ‘forehead’ of one of the eruptions. I took splinters of the wood.

Okay. A moss formation now has a ‘forehead’? ‘Tiny hands’, ‘moan’, ‘forehead’.

In terms of language we can see a pattern: she keeps anthropomorphising everything although she claimed to hate doing so.

Yet what we are seeing is not a contradiction—at least not in the sense of a plot-hole. It is the failure of language when faced with a reality that exceeds her current vocabulary. It is a sign of her innate need to understand reality by applying words that make it more known (and thus less terrifying).

The biologist had no accurate language to describe the composition, shape, and movement of that fungi or moss, and so she resorted to an aesthetic approximation: ’tiny hands’ or ‘forehead’; likewise, she couldn’t describe the sound on the marshes, and resorted to ‘moan’. This is exactly what linguistic relativity tell us: if we don’t have an accurate word, we need to approximate the meaning (with a single word or with a sentence) or create a new word.

And that is how Annihilation leverages linguistic relativity to challenge the biologist’s reality.

When language fails her, she doesn’t even try to come up with new names (like, a fancy but descriptive latin term). Instead, she keeps approximating the unknown with human-related vocabulary as metaphors for what she sees or hears: ‘hands’, ‘forehead’, ‘moaning’. The problem with those metaphors is that they impose human meaning onto Area X—which is not human.

After all, as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis posits, we perceive reality relative to the language used to describe it. In that sense, reality is a matter of perception. Therefore, if the biologist uses human-centred language… is she elevating or reducing Area X to a human’s level? Is she unknowingly accepting its sentience?

That’s where cosmic horror begins to slip into Annihilation. When the biologist no longer has the words to define what she’s experiencing and, due to that lack, reduces everything to human terms because reality exceeds her.

And it does, because the next challenge to her reality is:

The breakdown of sensory perception

Let us return to the beginning of the book, to chase another trail of clues. The first time the biologist sees the so-called tower, she describes it as follows:

[It was] a circular block of some grayish stone seeming to mix cement and ground-up seashells. It measured roughly sixty feet in diameter, this circular block, and was raised from ground level by about eight inches. […] A rectangular opening set into the surface of the block revealed stairs spiraling down into darkness. […] At first, only I saw it as a tower. I don’t know why the word tower came to me, given that it tunneled into the ground.

So here we have visual evidence, and likely tactile evidence as well, that this is just eight inches tall (that’s about 20cm tall)… yet she calls it tower? At least here she doubts her own choice of vocabulary albeit she continues to use it.

Could it be that perception contradicts logic and meaning? We may be onto something, so let’s keep digging.

Early on the book, when the biologist got close to the moss-written words (the ’tiny hands’), she inhaled some spores, which—in her own words—enabled “a truthful seeing”; the meaning of that is quite vague, but she comes to believe the “truthful seeing” allows her to perceive the true reality of Area X.

Fast-forward a few days, and the biologist returns to the tower. As expected, her “truthful seeing” allows her to perceive it differently:

[…] the tower was breathing […] and the walls when I went to touch them carried the echo of a heartbeat… and they were not made of stone but of living tissue. Those walls were still blank, but a kind of silvery-white phosphorescence rose off of them.

So this tower, which was described as made of coquina and stone, was actually made of… living tissue? Could this have been just another anthropomorphisation? Another verbal approximation due to language failure?

Maybe. Maybe not.

Annihilation takes a turn in the plot to give the biologist scientific evidence supporting her perception.

Within the tower, our protagonist finds the remains of the anthropologist surrounded by vials with samples of the Crawler—the plant-made being writing the moss-words on the tower’s walls. The biologist recovers one of these vials, and once out, puts the sample under a microscope. This is what she sees:

It was brain tissue—and not just any brain tissue. The cells were remarkably human, with some irregularities. My thought at the time was that the sample had been corrupted, but […] the surveyor’s notes perfectly described what I saw, and when she looked at the sample again later she confirmed its unchanged nature. […] Was [the Crawler] really human? Was it pretending to be human?

Both the biologist (affected by the “truthful seeing”), and the surveyor (allegedly not infected) saw the same: that the tissue of the plant-made Crawler was actually made of human brain cells.

I would call this odd except that oddities are the norm within Area X. Remember, this is a place that has been subtly, yet consistently, challenging the biologist’s understanding of the relationship between humanity and its surrounding environments.

Therefore, by giving her supporting ‘scientific evidence’, the author was actually teasing his character (and the reader!) with another question: how is that even possible? As I mentioned at the start, the book’s setting is Earth, and Area X is likely somewhere in the USA. Therefore, there is no way something can build a tower (tunnel?) out of human cells… right?

Were the biologist to accept that human tissue had been used (by Area X!) to build something, she’d need to accept a completely different relationship between humans and environment. Therefore, her reaction is the only sensible one—she doubts of her perception, and assumes the sample is somehow contaminated.

Yet she finds more evidence of this strange assimilation. She explains:

I examined the samples from the village: moss from the “forehead” of one of the eruptions, splinters of wood, a dead fox, a rat. The wood was indeed wood. The rat was indeed a rat. The moss and the fox… were composed of modified human cells.

So… do we, as readers, need to take the ’living tissue’ or the ‘brain cells’ or even the ‘modified human cells’ literally? Or is it metaphorical? Is the biologist’s perception completely messed up, or is there a hint of truthfulness in there?

What a complex question.

The literal interpretation holds because she has several samples, right? She put them under the microscope, had someone confirm her observations. The literal should be true—and here is when another bit of cosmic horror slips in, bringing back that question I asked before: what does it mean? Why, within Area X, are there animals and moss built from human cells?

Creepy. Let’s pause that idea for a minute.

We need to tackle the metaphorical side. In this interpretation, the ’living tissue’ or the ‘human brain cells’ could be an example of perception bias—a cognitive bias defined as: “the act of perceiving things around us with a subjective approach that can lead us to make incorrect judgements”7. Namely: the cells could be something unknown, but they’re so biologically close that the biologist calls them ‘modified human cells’. In this sense, we can appeal to the failure of her language, and how her constant use of humanising adjectives challenged her perception of Area X until it became sentient in her mind.

We can link these two interpretations (literal and metaphorical) to the concept of “truthful seeing”… and I’m going to ask something unsettling to bring back the cosmic horror:

What if Area X is actually building stuff out of the humans Southern Reach sends in the expeditions? What if “truthful seeing” means perceiving Area X as it actually is (aka, a dangerous environment that uses humans as material) rather than as the biologist needed it to be (an interesting but known transitional environment)?

In that vein: what if the biologist cannot accept reality? What if she has to keep believing that her perception is skewed, simply because the truth of Area X breaches every single belief humanity has?

That’s the point, truly.

Area X refuses our anthro-centric worldview.

Let us be honest: we humans have an awful tendency to navel-gaze and define everything in human terms.

On the one hand, we mold the environment to what we need. If a river is not quite what we need, we carve it wider, deeper, or build a dam and flood a large territory because who cares, we actually needed it. If there is a forest, we chop it to build a highway. If there is no island for a fancy hotel, we build one. Hell, we even sink stuff into bays and seas—purposefully so!—as tourist attractions! We are used to the environment being (somewhat) defenseless against humanity’s whims.

On the other hand, we also bend perception into human-likeness. For example, there are loads of research about whether animals experience emotions, whether they can see as we see, whether plants can be sad or happy. Even in creative writing, we define aliens as non-humans, and body-shapes similar to ours as ‘humanoids’ or ‘anthropoids’. Even ’neural networks’ in AI are called like so because they were built to approximate how a human brain works.

Can we see where I’m going? Everything we humans do is anthro-centric. Beyond the physicality of altering the ecosystem, and at an intellectual level, we are constantly trying to bend reality into what we understand of ourselves. But what if animals have a different framework for emotion? What if they don’t experience love or fear but emotions we have never labelled simply because we remain obtusely focused on our athro-centric view of the universe?

That is exactly the point Annihilation is trying to make. It leads the biologist (and through her, the reader) to realise that, to Area X, humans are irrelevant.

Yet as before, when faced with this conundrum, the biologist takes the only reasonable (pun intended) path of action: she begins to craft explanations meant to bend Area X into her anthro-centric understanding. For example, while travelling towards the Lighthouse, she begins to think about the Crawler’s moss-words and their purpose, eventually writing that:

I had seen the faint skeletons of so many past lines of writing that one might assume some biological imperative for the Crawler’s work. This process might feed into the reproductive cycle of the Tower or the Crawler. Perhaps the Crawler depended upon it, and it had some subsidiary benefit to the Tower.

The biologist was desperately trying to force the Crawler and the Tower into a symbiotic relationship just like those she studied before. The problem here is twofold:

She doesn’t have data; that whole paragraph I just read is guesswork at best. Worse off: it’s not the only one, since she keeps guessing without supporting evidence—and the explanations become esoteric.

She doesn’t even challenge those guesses, accepting whatever theory she arrives to: psychological, ecological, alien.

And you know what? What she was doing is deeply human: we want interpretation, not raw data. When faced with the impossible and what disproves our anthro-centric framework of existence and comprehension, we cling to whatever scrap of meaning and sense we can craft.

The biologist was not finding answers by crafting those theories. She was manufacturing a sense of control: a reality in which humans are not just material. One with a semblance of similarity and comfort. One that could be more known.

And you know why?

We humans do not want to encounter the unknown—we want to turn it into something known. Area X denies that comfort, exceeding the biologist’s (and thus, the reader’s) perception and comprehension to forbids something worse: identity.

Because within Area X, there is no individual purpose.

To Area X, humans are just clay, remember? The creepy, literal interpretation of the ‘brain tissue’ and the ‘modified human cells’ turned into moss and a fox. If within Area X humans are just clay, then there is no existential meaning or purpose—and that is incredible against everything we humans believe.

There are clues about this in the book, so let us revisit them.

As the biologist explained early on, the expedition members “were meant to be focused on [their] purpose, and anything personal should be left behind”. Thus, it is easy to assume that if Southern Reach was sending expeditions into Area X, the ‘purpose’ of each was to understand the region and the things within it. It may be vague, but it’s purpose—a mission, a motivation.

Following that logic, once the team finds the tower, the first thing they ponder is its purpose. The biologist writes:

With the tower, we […] had no sense of its purpose. And now that we had begun to descend into it, the tower still failed to reveal any hint of these things.

And so, Area X begins to eat away the concept of ‘purpose’. It continues to do so, since upon encountering the crawler’s moss-words, the biologist wonders about their meaning:

Did [the words] come from longer accounts of some sort, possibly from members of prior expeditions? If so, for what purpose? And over how many years? […] What role did the Crawler serve? […] What was the purpose of the physical “recitation” of the words? Did the actual words matter, or would any words do?

It’s so upsetting, don’t you think? Nothing within Area X has a purpose! Not even the expedition, because as the plot develops, Area X chips it away.

In the biologist’s own words, she was despairing because what she saw “resisted all logical explanations” by not having a clear (aka, human-understandable) goal… and because of that, she had no purpose either. After all, what good is a biologist sent to study a region, to only come up with “I don’t know” answers? To put things under the microscope and be incapable of understanding them? To be unable to even describe the place she’s in? What’s the point of having studied so much to comprehend so little?

That loop of questions around purpose—this cosmic dread—builds on the biologist until she begins crafting those guesses we discussed before: attempting to turn the unknown into the known, because if everything around her made sense, then her purpose (to understand the biology of Area X, to complete an expedition and come up with results) was fulfilled. If that was fulfilled, then she was in control: of herself, and Area X.

Let us admit something: we, humans, have an insatiable need to know why we are here.

That’s the big existential dilemma, isn’t it? What is our purpose? Are we destined to be just this or more? But what is more? Are you reaching fulfillment by doing something? Are we answering our call (and whatever that may be)? Do we know what that call is? Throughout our lives we try so hard to find that meaning, be it by learning and trying new things, by resorting to faith, to science, to philosophy, to anything that can makes us feel less small, less irrelevant.

Know something: we humans fear irrelevance, not death. Irrelevance in the sense of lacking a personal purpose. You could even say we alter the environment, building structures that will survive us, only to be remembered, to leave a mark, a bit of evidence that we are not—and have never been—irrelevant.

Purpose is so thoroughly linked to identity and selfhood that, throughout history, we crafted an entire branch of philosophy dedicated (solely!) to think about the purpose and the meaning of life. This is called existentialism.

Existentialism

Therefore, let’s bring in a bit of existentialism, as I promised:

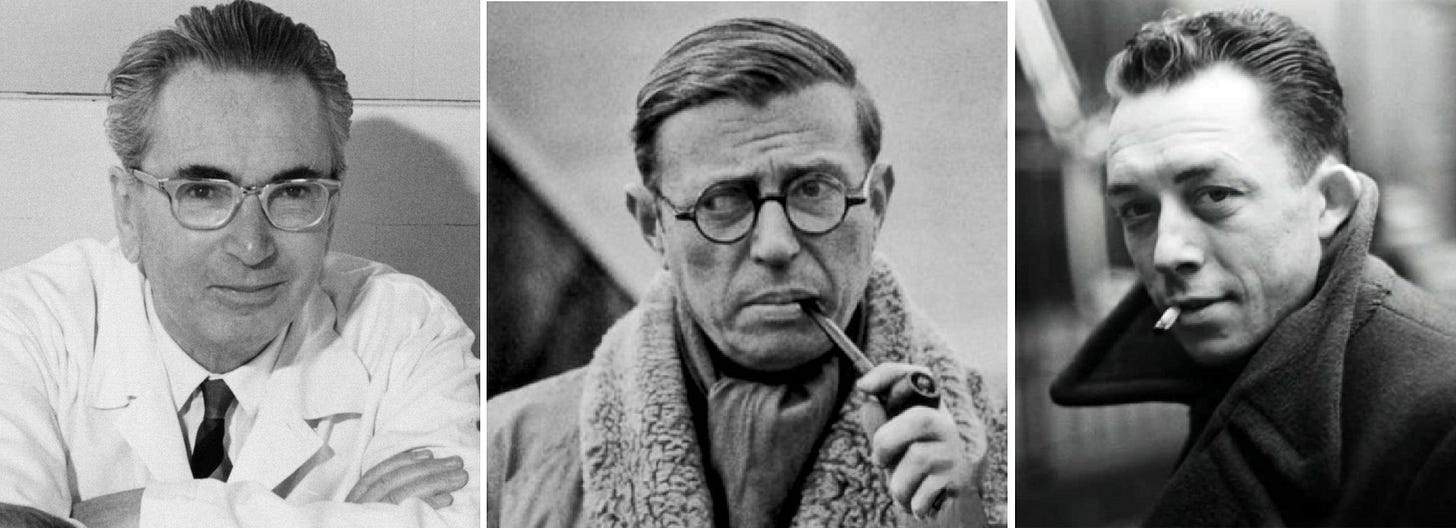

Viktor Frankl’s book: Man’s Search for Meaning. He famously wrote that “He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how”, suggesting that meaning isn’t just a philosophical nicety but existentially necessary for psychological survival. To him, the quality of our life doesn’t matter as long as we know what we live for.

Jean-Paul Sartre, who stated that “existence precedes essence”. He argued we’re born without meaning only to later in life define it ourselves. However, this means we are responsible for inventing purpose in a meaningless world.

Albert Camus, in The Myth of Sisyphus argued that life’s lack of inherent meaning creates a tension between our craving for purpose and the universe’s silence. Camus wondered whether we could live without appealing to a higher meaning, only to reach one conclusion: we need to embrace the absurd, to live in full awareness of life’s purposelessness, without retreating to false hopes.

Putting that in the context of Annihilation:

From Frankl we know that people usually construct purpose to stay grounded—which is exactly what the biologist was trying to do with her incessant guesswork.

From Camus we can take something else: the acceptance for the absurdness of Area X—and whether that ties into the title of the third book, Acceptance is something for another episode. Camus would ask how should the biologists live in full awareness of Area X’s absurdness? Of her lack of purpose while within Area X?

Finally, Sartre’s “existence precedes essences” also links into the books terrifying question: what if humans are no longer even able to craft a purpose because Area X denies it? Should that be embraced or denied? In that sense, can that “truthful seeing” relate to accepting humanity’s role within Area X?

Wouldn’t that be the ultimate loss of meaning and purpose? Could any human live knowing that, within Area X, we are not the kings bending reality to our shape, but being shaped by it?

Those are deeply unsettling, cosmically dreadful questions, aren’t they? Yet that is the point of the book, and how it subtly, quietly, posits those questions.

Existentialism, as a philosophy, is obsessed with purpose because it starts from a vacuum in which humans are small and lost in the cosmic narrative, thus burdened with the impossible task of making meaning inside that blank space. Annihilation doesn’t quite follow the rules of existentialism as a philosophy, since it asks something even more dreadful: what if we are not given the choice to craft meaning?

In Sartre or Camus, meaning is difficult, absurd, personal… but still possible. In Annihilation, the biologist tries to make meaning—tries to classify, rationalise, theorise—and Area X does not care. Eventually she gives up and goes to explore—up the shore, to find a boat to cross into an island… but even that has a purpose: to find her husband, who was part of the previous expedition, and whose journal said he went to the island.

So here she is, having lost all her prior purposes and crafting a new one just to keep existing in the off chance that, having a purpose, will prevent Area X from using her as clay.

Do you know why? Because without purpose we reach the dissolution of the self. Curiously (and likely intentional) the last chapter of the book is called Dissolution.

Although there are a few academic papers on dissolution of the self8, we can grossly summarise it as the loss of individuality to become part of a whole—whether that is a group of peers, society, or even something like Area X. Thus, the biologist needed a meaning, one linked to her existence and her life as an individual, not to be annihilated. In her own words:

[…] when you see beauty in desolation it changes something inside you. Desolation tries to colonize you.[…] That’s how the madness of the world tries to colonize you: from the outside in, forcing you to live in its reality.

As I see it, the ‘desolation’ here is the lack of purpose: the barren left after accepting the absurdness of a purposeless place (namely, Area X). The ‘beauty’ is that existence, in that way, could be simpler—no longer chasing fulfilment, no longer wondering what we want out of the years we have left to live. The ‘madness of the world’ could very well refer to Area X, and the ‘colonisation’ could be a metaphorical reference to the spores she inhaled.

In other words, this paragraph implies that Area X forced every human that went into it to lose their selves, their identities, their name and purpose to be just a building block: cells, clay. Meaningless. Irrelevant.

We could say that VanderMeer took existentialism to the nth degree into post-humanist cosmic horror: it’s not only about having to invent meaning, but having that meaning be utterly irrelevant.

Ultimately, Annihilation is a challenge to humanity’s perennial navel-gazing. It confronts us with the terrifying idea that the universe is not hostile—it simply doesn’t care about us. It forces us to face the absurd truth that our search for meaning may itself be meaningless. It reminds us that our frameworks—language, identity, purpose—are too small to contain a reality so vast. It exposes the cosmic horror of a world that continues, evolves, and transforms… with or without us.

Outro

Before closing off, allow me a few last remarks.

There is so much to discuss around the moss-words the Crawler writes. The quote is quite poetic and extensive, and you can read it from an existentialist standpoint. You can also read it as a chant outlining how Area X uses humans. It could be an episode of its own, and so I had to skip this all together.

The fact that Area X uses humans as clay is very interesting. There is a creepy detail about copies of humans in a human-semblance… but then again, it could be an episode of its own. I couldn’t fit this here.

The “truthful seeing” and the “brightness” the biologist feels (something I purposefully left out) could speak of symbiosis and finally letting go of her individualism, to willingly accept the dissolution of her self.

Linguistic relativism is one of my favourite topics, and I discussed it twice before in this podcast: on my episode on Babel-17 and in one about Orwell’s Newspeak. Both are shorter than this, so you may want to check them out.

To close off, if you liked this episode, please check my Substack at liviajelliot.substack.com. I post weekly thematic analyses (and you can find the episode’s transcripts there), literary analyses, and practical writing advice for speculative fiction writers.

As a bonus for subscribing, you’ll get the free ebook of my novella titled The Genesis of Change. It is a blend of cosmic horror and philosophy, with a touch of existentialism (Sartre, Kierkegaard) and stoicism. You may enjoy it.

Thanks for listening, and happy reading~

A recommended reading about the subgenre (thus, non-fiction) is "Writing Ecofiction: Navigating the Challenges of Environmental Narrative" by Kevan Manwaring. It's available in Springer Nature: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-55091-1

"Names, Identity, and Self" by Kenneth L. Dion (published in 1983), also includes an interesting recap of research around the link between names and identity up until then. It was published on "Names: A Journal of Onomastics" by Taylor & Francis: https://doi.org/10.1179/nam.1983.31.4.245

I am not a biologist and certainly not a geologist. This text by the University of West Georgia via GALILEO Open Learning Materials is pretty down-to-earth.

Writers' Digest has an interesting piece called "What Is Cosmic Horror in Fiction?" written by its managing editor, Moriah Richard. Another useful article is "Your Introduction to the Cosmic Horror Genre" by Sarah S. Davis and published in BookRiot.

"Living Language: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology" by Laura M. Ahearn, published by Wiley-Blackwell in 2012. Link here. I have only read sections of it.

The Standford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy is one of the best resources out there. It is dry as nothing else, but it's free to read and fully online; I'll take the trade off. The article I was quoting is "The Linguistic Relativity Hypothesis".

Bias is a theme that features prominently in my own writing, but I'll refuse to swarm you in additional readings. In this episode, I was quoting, "What is Perception Bias?" published in Research Prospect.

Difficult to find, but Kenneth J. Gregens "The Dissolution of the Self" (1991) is pretty interesting, and centred around social saturation. Joseph Gemin's paper "The Dissolution of the Self in Unsettled Times: Postmodernism and the Creative Process" frames it around creative behaviour. You could even consider Kierkegaard's "self as a task" and how failing to complete that task can lead to irreconciliable conflicts related to our selfhood.

Share this post